FWC offers videos to educate Floridians on how best to avoid conflicts with bears

As part of a continuing effort to reduce conflicts with bears, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) is releasing two new videos in the “Living with Florida Black Bears” series, designed to educate the public about how to safely coexist with bears in Florida.

The “Cause for a Call” video outlines when and how people can reduce conflicts with bears by taking simple steps such as securing trash and other attractants.

The “BearWise Communities” video describes how to make a neighborhood “BearWise.” BearWise communities work to coexist with bears. This video educates residents on when and how to report bear conflicts or sightings, and how to secure food items that attract bears to a neighborhood.

BearWise Communities from My FWC on Vimeo.

Unsecured trash and attractants, such as bird feeders, are the number one cause for bears coming into contact with people. This summer FWC researchers, in partnership with Dr. Joseph Clark, a leading black bear scientist, employed cutting-edge modeling to confirm that Florida’s robust black bear population is estimated to be over 4,000 bears. More bears in Florida means more chances for human-bear interaction, which can be dangerous.

The new videos are being added to the existing “Living with Florida Black Bears” series, which already includes the following videos:

- How to Make Your Wildlife Feeders Bear-Resistant

- How FWC Conducts Bear Population Estimates

- A Day in the Life of a Florida Black Bear

- How to Protect Pets and Livestock from Bears

The FWC plans to release more bear-related videos in the coming months. The short videos help meet the information needs of a busy public.

To view the “Living with Florida Black Bears” video series, visit MyFWC.com/Bear and click on “Brochures & Other Materials.”

In addition to educational efforts, the FWC is providing financial assistance to local communities so residents and businesses can take actions to reduce human-bear conflicts. To ensure Floridians have the resources necessary to properly secure their garbage, the FWC is currently working to distribute $825,000 to communities to become more BearWise by funding bear-resistant equipment and other methods to reduce conflicts. These efforts are in addition to our already robust Bear Management Program, which includes over 100 staff working year-round to educate people about bears and respond to human-bear conflicts. Read more at MyFWC.com/news and click on “News Releases,” “Oct. 2016” and scroll to “FWC receives 19 proposals…”

Bear videos available at: https://vimeo.com/album/3605088

Bear Resistant Wildlife Feeders from My FWC on Vimeo.

—————————————————–

Gopher tortoises find refuge at Nokuse Plantation

More than 3,400 tortoises thrive at preserve in Walton County

In its natural habitat many years ago, the gopher tortoise was a thriving species in Northwest Florida. This medium-sized tortoise with a gray or amber to dark brown shell is as old as the sandhills it loves. It is one of the oldest species on Earth, dating back to the Pleistocene Epoch – the Ice Age. Gopher tortoises are long-lived reptiles that occupy upland habitat throughout Florida including forests, pastures, and yards. They dig deep burrows for shelter and forage on low-growing plants. Gopher tortoises share these burrows with more than 350 other species, and are therefore referred to as a keystone species.

Despite surviving the perils of geological time, during just the past three decades, the rate of decline for the species exceeded 30 percent, prompting the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) to list the gopher tortoise as threatened, and taking regulatory action to help protect the species. To assist in protecting the species, FWC established a management plan for the tortoises, which includes relocation of the species from development areas.

The historic declines of the gopher tortoise throughout the southern portions of the State have been caused by land development. In the Florida Panhandle it was due to severe and unsustainable human harvest of tortoises for their meat. Click here to continue

—————————————————–

Why prescribed burns are good for the forest

Ever wonder why Forestry Service and State parks set fire to the forest? The answer is quite simple – to preserve a healthy forest habitat. Not only does the wildlife thrive after a burn, the forest floor rejuvenates to a proper natural balance.

Ever wonder why Forestry Service and State parks set fire to the forest? The answer is quite simple – to preserve a healthy forest habitat. Not only does the wildlife thrive after a burn, the forest floor rejuvenates to a proper natural balance.

Many of Florida’s ecosystems such as longleaf pine sandhills, flatwoods and sand pine scrub cannot survive without fire. It releases nutrients and allows light into the forest allowing regeneration of native plants that feed wildlife. If the forests are not burned regularly, leaf litter and shrubs accumulate, choking native fire-adaptive plants. This starves wildlife and creates the risk of uncontrollable wildfires.

Prescribed fire is one of the most versatile and cost effective tools land managers use. Prescribed fire is used to reduce hazardous fuel buildups, thus providing increased protection to people, their homes and the forest.

A Balancing Act

Scientists have studied forests and fires to determine the secret of nature’s success in attaining this necessary balance. They have learned that a “natural” fire results from a certain fuel condition. Some forest types produce and accumulate fuels faster than others, some decompose fuels more readily than others. However, at some point in time, every forest type has fuel of the right quantity and quality for that forest to be ‘ready’ to burn.

Information courtesy Agriculture and Consumer Services Florida Forest Service, Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

—————————————————–

North Walton pitcher plant bog boasts international fame

One native Sarracenia hybrid named after landowner

Tucked behind the fence line of a North Walton County farm is a wetland bog with international intrigue. A pitcher plant bog that is, along the banks of Walton resident Leah Wilkersons’ pond.

Since the early 1930s, Wilkerson’s family lived and worked their cattle ranch on 72 acres of rolling hills in the New Harmony area. Early on, Leah’s father dug a multi acre pond and burned the surrounding land to create healthy cattle grazing pasture.

“He didn’t believe in planting a pasture, he burned,” Wilkerson said.

Over the years, the good land stewardship created the perfect environment for the natural growth of wiregrass and pitcher plants.

“I had no idea the burning helped the pitcher plants to grow,” Wilkerson said.

Over the years the pitcher plant field grew to several acres and started garnering quite a bit of attention. Passers by would stop, gawk, take photos and sometimes help themselves to the plants.

“It was ridiculous; they would stop, come up in the yard and just grab plants,” Wilkerson remarked. Click here to continue

—————————————————–

Play it safe when recreating in fresh and brackish water

The onset of warm weather in the spring is when Florida’s alligators and crocodiles start getting active, and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) reminds Floridians and visitors to be cautious when having fun in and around water.

Florida is home to two native crocodilians: the American alligator, which is found in all 67 counties, and the American crocodile, which may be found in coastal areas of the Keys, Southeast and Southwest Florida. Both species have shared Florida’s waters with people for centuries.

The FWC recommends keeping pets away from the water. There are other precautionary measures people should take to reduce potential conflicts with alligators and crocodiles, and they are available in the “Living with Alligators” brochure.

Click here to download brochure

The FWC advises if you have concerns with an alligator or crocodile that poses a threat to you, your pets or property, call the FWC’s Nuisance Alligator Hotline at 866-FWC-GATOR (392-4286).

Alligators and crocodiles are an important part of Florida’s heritage and play a valuable role in the ecosystems where they live. For more information on alligators and crocodiles, visit MyFWC.com/Alligator. Click here to continue

—————————————————–

Sandhill crane visitors a welcome sight for local bird lovers

Clara Pittman of North Walton County looks forward to the special wintering guests she enjoys watching arrive in late fall. For the last five years, sandhill cranes have been migrating to the wetlands near her home just south of Lake Jackson in North Walton.

Typically arriving in mid-December and staying until mid-March, the cranes are a welcome sight, and have been flocking to the area in large numbers.

“I have seen as many a three dozen in the wetlands; I enjoy watching them,” Clara said.

With a wingspan of up to 78 inches and standing more than 3 feet tall, the sandhill crane (Grus canadensis) is one of the largest birds in North America. There are several subspecies of the sandhill crane with the Lesser Sandhill (Northern) migrating from the northern U.S. and the Greater Sandhill (Southern) year-round residents in southern Florida. Click here to continue

—————————————————–

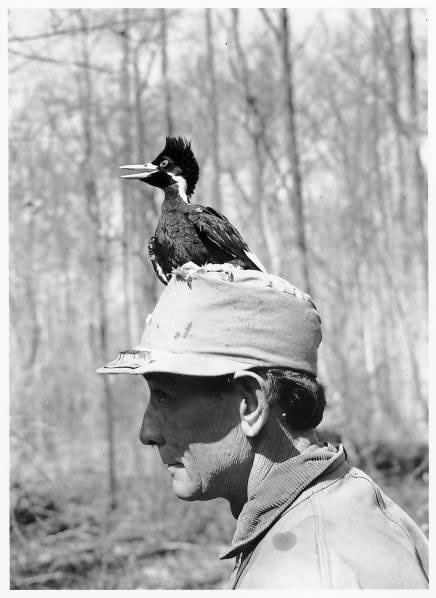

Choctawhatchee Audubon Society explores ivory-billed woodpecker habitat in Walton County

Choctawhatchee River Basin provides excellent birding opportunities

The existence of the ivory-billed woodpecker has been a disputed subject for many years. Thought to be on the brink of extinction since the 1940s, there has not been a documented sighting since 2005. However, the largest woodpecker in North America has been the quest of many a birder both on an amateur and academic level.

If the elusive ivory-billed woodpecker (IBWO) exists, the Choctawhatchee River basin in Walton County is the perfect habitat to explore the possibilities. An alluvial river, the Choctawhatchee River is characterized by a broad floodplain and seasonal flooding. Its old growth bottomland hardwood forests has drawn ornithologists searching for the IBWO for several years.

In 2005, Dr. Geoffrey E. Hill, Auburn University ornithology professor, and two research assistants, Tyler Hicks and Brian Rolek, took a kayak trip down the river. Within an hour of launching their boats, they heard a bird hammering loudly on a tree. When the bird flew off through the canopy, Brian got a clear view of a large woodpecker with white on both the upper and underside of the trailing edge of the wings; a unique characteristic of the IBWO. Although members of the search group are convinced that ivory-billed woodpeckers persist in the swamp forests along the Choctawhatchee River, they conceded that the evidence fell short of definitive. Definitive evidence must come in the form of clear, indisputable film, digital image, or video image of an IBWO. They continue their studies on the river to this day. Click here to continue

—————————————————–

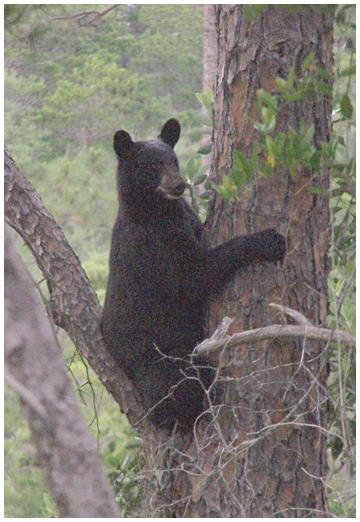

Living with Florida black bears

The presence of bears is not necessarily a problem or a threat to your safety. For many people seeing a black bear is a thrilling, rewarding experience.

Problems arise when bears have access to food sources unintentionally made available by people such as pet foods, garbage, barbecue grills, bird seed or livestock feed. Bears are adaptable and learn very quickly to associate people with food. Black bears are normally too shy to risk contact with humans, but their strong food drive can overwhelm these instincts.

The Florida black bear is a unique subspecies of the American black bear, and is listed as a threatened species in Florida and is the state’s largest land mammal. Black bears once ranged throughout Florida but now live in several fragmented areas across the state.

Since the 1980s, the black bear population has been expanding along with our human population. Florida has grown from 5 million residents in 1960 to close to 18 million today and is projected to reach almost 36 million by 2060. Urban sprawl is encroaching on traditionally remote areas and bringing people into prime bear habitat. As a result bears and people are encountering each other more than ever.

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) has a wildlife alert number and also encourages state visitors and residents to contact FWC Regional Offices for assistance on what to do if they see a bear. Now that the populations of bears and humans have increased and outreach efforts have made these resources more widely known, the bear-related calls have reached a record number with 2,674 in 2007. Many of these calls are simply sightings or reports of a sick or injured bear, but many report problems such as a bear in the garbage, a bear at the birdfeeder or other property damage.

—————————————————–

A guide to Florida snakes

Florida has an abundance of wildlife, including a wide variety of reptiles. Snakes, and their cousins the alligators, crocodiles, turtles and lizards, play an interesting and vital role in Florida’s complex ecology. Many people have an uncontrollable fear of snakes. Perhaps because man is an animal who stands upright, he has developed a deep-rooted aversion to all crawling creatures. And, too, snakes long have been use in folklore to symbolize falseness and evil. The ill- starred idea has no doubt colored human feelings regarding snakes. Whatever the reason for disfavor, they nonetheless occupy a valuable place in the fauna of the region. Click here to continue

—————————————————–

Ugh… the dog flies have arrived in the Florida Panhandle

When fall comes to our area, those refreshing weather fronts will move through from the north bringing lower humidity, lower temperatures and the infamous dog fly. The stable fly, known as the dog fly in Northwest Florida, is a blood feeding fly that is a nuisance to man, pets, and livestock. From August through November the dog fly congregates on the Florida Panhandle beaches. This fly originates from farming areas in southern Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia and northern Florida and rides the northerly winds associated with cold fronts that move through our area. Click here to continue

When fall comes to our area, those refreshing weather fronts will move through from the north bringing lower humidity, lower temperatures and the infamous dog fly. The stable fly, known as the dog fly in Northwest Florida, is a blood feeding fly that is a nuisance to man, pets, and livestock. From August through November the dog fly congregates on the Florida Panhandle beaches. This fly originates from farming areas in southern Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia and northern Florida and rides the northerly winds associated with cold fronts that move through our area. Click here to continue

—————————————————–

Keep up with what’s happening with the sea turtles!

—————————————————–

It’s that time of year again, and those blood-thirsty yellow flies are here… here are some tips for armoring yourself

In Florida, the name “yellow fly” is used to describe about a dozen different species of yellow-bodied biting flies. “Yellow flies” readily attack man and are usually abundant in Florida with peak annoyance occurring in May and June. “Yellow flies” are in the family known as Tabanidae. All tabanids go through an egg, larva, pupa and adult stage, referred to as “complete metamorphosis,” the same development process that mosquitoes go through. Tabanids lay egg masses containing 50 to several hundred eggs. Most species deposit their eggs around ponds, streams or swamps on overhanging vegetation such as grasses or cattails. Click here to continue

In Florida, the name “yellow fly” is used to describe about a dozen different species of yellow-bodied biting flies. “Yellow flies” readily attack man and are usually abundant in Florida with peak annoyance occurring in May and June. “Yellow flies” are in the family known as Tabanidae. All tabanids go through an egg, larva, pupa and adult stage, referred to as “complete metamorphosis,” the same development process that mosquitoes go through. Tabanids lay egg masses containing 50 to several hundred eggs. Most species deposit their eggs around ponds, streams or swamps on overhanging vegetation such as grasses or cattails. Click here to continue

—————————————————–

Four Florida caterpillars you need to avoid

The four major stinging caterpillars occurring in Florida are the Puss Caterpillar, Saddleback Caterpillar, IO Moth Caterpillar and Hag Caterpillar. Some less common ones also occur in the state. These caterpillars do not possess stingers, but have spines (nettling hairs) that are connected to poison glands. Some people experience severe reaction to the poison released by the spines and require medical attention. Others experience only an itching or burning sensation.

Stinging caterpillar’s feed on many pants, but they seldom are present in large enough numbers to cause serious damage. Their stings, rather than feeding, pose the primary threat. That’s why it’s important to learn to recognize and avoid these cantankerous crawlers. My information on stinging caterpillars was provided by Extension Entomologist Dr. Don Short and Dr. D. E. Short of the University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences

The puss caterpillar is stout bodied, almost an inch long, and completely covered with gray to brown hairs. Under the soft hairs are stiff, poisonous spines. When touched, the spines break off in the skin, causing serve pain. The saddleback caterpillar has a more striking appearance. It’s brown, with a wide green band around the middle of the body. There’s a large brown spot in the middle of the green band, giving the appearance of a brown saddle on a green blanket. The saddleback may exceed and inch in length, and is stout bodied. The main poison spines are born on pairs of projections near the front and rear of the body. There’s a row of smaller stinging organs along each side.

The IO moth caterpillar is pale green, with yellow and reddish to maroon stripes along the sides. It often exceeds two inches in length, and is fairly stout bodied. The poisonous spines, which form rows of bands across the body, are usually yellow with black tips.

The light brown hag moth caterpillar has nine pairs of variable length protrusions along its body, from which poisonous spines extend. The protrusions are curved and twisted, giving the appearance of disheveled hair of a hag.

Most contact with stinging caterpillars occurs in the spring and summer. As might be expected, children, campers, and gardeners are most frequent victims. When playing or working outdoors in infested areas, it pays to wear a long-sleeved shirt, long pants, and gloves.

Reactions to caterpillars poison vary with an individual’s sensitivity. Itching, burning, swelling, and nausea may be experienced. In severe cases, fever, shock, and convulsions may occur. If a person has a history of hay fever, asthma, or allergy or if allergic symptoms develop a physician should be contacted immediate. In cases of milder reactions, a strip of adhesive tape should be placed on and pulled off the affected area repeatedly to remove the spines. Then, apply ice packs, followed by a paste of baking soda and water.

Since so few stinging caterpillars are normally found on plants around the home mechanical methods usually offer the easiest means of control. Just carefully remove and crush the caterpillars, or knock them into a pan of kerosene. If a pesticide is needed, bacillus thuringiensis (Bt), seven or Malathion may be used in accordance with label directions for caterpillar control.