Gentle giants can be seen in the Choctawhatchee Bay and as far west as Escambia County

By Stan Kirkland,

Public Information Coordinator, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Northwest Region

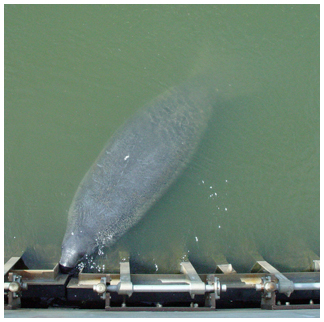

It’s been six or seven years since a guy in a plaid shirt and shorts walked into our Deer Point office one summer morning and said a big manatee was hanging around the Deer Point Dam. I grabbed my camera and drove the quarter mile to the dam and the guy was right. There was a 10-11 foot adult manatee slowly swimming next to the draw down gates.

The manatee hung around long enough for me to snap several photos and then slowly worked its way down the cement-lined channel and disappeared into North Bay.

Last June a mature female manatee and her 3-4 foot calf spent several days around Bailey Bridge in North Bay and the Grand Lagoon area near St. Andrews Pass before departing to parts unknown. I still remember a photograph that ran in the Panama City News Herald several years ago where someone flying over the beaches area snapped an amazing photo of 5-6 manatees leisurely swimming several hundred feet off Shell Island.

While manatees spend the majority of their time in warmer waters on Florida’s east and west coasts, we get a surprising number of these lumbering mammals who venture north each summer. Sightings and reports are common in the St. Marks, Aucilla, and Apalachicola Rivers, Lake Wimico, which is well off the Apalachicola River, St. Andrew Bay, and sometimes Choctawhatchee and Escambia bays.

The Florida manatee is on the states imperiled species list and is holding its own in numbers, despite the cold-induced deaths of several hundred animals the last two winters. In January staff of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s (FWC) Fish and Wildlife Research Institute completed its annual synoptic manatee survey on the states’ east and west coasts. Although not a total count, researchers located 4,840 manatees, mostly in warm water refuges. Just how many manatees they missed is anyone’s guess.

Manatees have wrinkled, gray-brown, spongy skin and are herbivores. Adults can eat 100 pounds or more of vegetation a day as they cruise around. They come to the surface and get a breath of air every three-four minutes when they’re active. When they’re are inactive it can be 20 minutes in between breaths. Adult manatees can easily weigh over 1000 pounds and grow to 12 feet in length.

The air-breathing marine mammals do quite well in Florida Panhandle waters in late spring and summer months when water temperatures are high but when water temperatures drops below 70 degrees F in the fall, these huge animals have to head south. Otherwise, they can succumb to what biologists say is “cold stress” and die.

Manatees have a very interesting time of development. A female manatee doesn’t breed until about age 10. When the mating ritual occurs near urban areas, it’s no wonder it draws the attention of people. A pod of a half-dozen or more males may aggressively pursue a lone female into shallow water only inches deep for the right to breed. People who see the ritual think the animals are in distress, or beaching themselves like dying whales, but no so. It’s just manatees being manatees.

Manatees give birth to a single calf every three-four years. The calf nurses for a year and may hang around the mother for another year before heading out on its own.

The biggest factors in manatee deaths each year are vessel collisions, red tide outbreaks and cold weather. While there’s not much anyone can do about the latter two causes of death, slow or idle-speed zones for boats are used on a number of waterways in south and central Florida to reduce manatee deaths.

Early in the history of this country manatees were looked at a source of food. Thankfully, that’s not the case anymore. Today, they are protected by both state and federal law, with severe consequences for anyone who would harm one of these gentle giants.